Margery’s voice

It was an archive that nobody has looked at for ages, full of boxes holding legal documents, wills and deeds; hardly exciting if you don’t know what to look at. Even if you did know, all of the texts were written in Low German and Latin. Since the 19th century, nobody had paid the archive in Gdansk any attention.

Nobody, that is, until medieval English literature and culture professor Sebastian Sobecki paid a visit. He was looking for a sign – any sign – of the family of the famous 15th century mystic and writer Margery Kempe. He found it in a mention of her son, whom he knew had been living in Gdansk at the time. The letter states that he was travelling to the English town of Lynn – where his mother lived – with his wife and daughter to collect a debt.

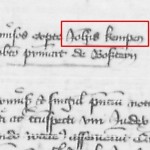

- A passage of the letter found in the archives, mentioning the name ‘Kempe’. Courtesy of the National Archive in Gdańsk.

A huge find

Sobecki recalls the rush of excitement he felt when he first set eyes on the document, as well as the doubt. Was it really from a member of the Kempe family that he was looking for, or could it perhaps be refering to a place – Kampen – instead? Sobecki quickly asserted this was not the case. He really was onto something.

It’s a huge find that Sobecki will publish later this year in the research journal Studies in the Age of Chaucer. It’s significant not because of the document itself, but because it gives historical context to the only surviving copy of the Book of Margery Kempe written in the 1430s.

‘I teach her almost every year to my students. She was such a character!’In it, Margery describes her life, her many pilgrimages and, importantly, her visions and conversations with Jesus. The Book is one of the very first English works of prose and is even more special because it’s the rare voice of a woman, speaking from all those hundreds of years ago.

And what a woman she was. ‘She’s always been one of my favourites’, Sobecki says enthusiastically. ‘I teach her almost every year to my students. She was such a character!’

Visions

Anyone who reads the account of Margery’s life will appreciate that observation. After giving birth to her first child, Margery fell ill and began having visions for months on end. Devils visited her continuously and tried to convince her to forsake her faith. Her illness got so bad that she was chained up in a room. But Jesus visited her and comforted her.

- An illustration from ‘The Book of Margery Kempe’. After she gave birth, Margery began having visions, both of Jesus and devils.

After her recovery, the visions kept coming. She provoked people around her by writhing, wailing and sobbing in public. She dressed in white – very presumptuous for a married woman – and threw herself at priests onto whom she projected Christ himself. The archbishop of York paid people to get rid of her after a public discussion in his church. She was accused of heresy and locked up. She ogled the men around her, notwithstanding her wish to live a chaste life.

Sobecki loves it all. ‘She was a woman in desperate need of attention’, he believes. ‘However, she was also very smart and undertaking’, he says with a smile. ‘She spoke to Jesus often, she claims, but only shared the information that suited her with others, such as when she negotiated a chaste marriage with her husband and he wanted to sleep with her one last time. ‘I first have to ask Jesus’, she said, and started praying. Jesus actually did give her permission to do it, but she never told her husband’, Sobecki says.

Co-authorship

Yet it’s hard to determine how much of the account in the Book is actually hers. As a woman, Margery was unable to read or write much, and certainly could not have written a book like this. At first, she dictated it to an unknown scribe, who died. Later, she asked her priest and confessor to transcribe the notes, but he didn’t want to do it, because the notes were – as he said – unintelligible. Still, he eventually took on the job.

Is it a woman’s tale filtered through a male religious lens?‘However, he has anonymised a lot of the information. He calls Margery’s hometown Lynn ‘N’, for example. Also, there are theological issues raised that can’t have come from her. He probably did that because he wanted the Book to have a universal appeal, like a saint’s life.’

So is it really the priest’s book or is it more of a co-authorship? Is it a woman’s tale filtered through a male religious lens? That’s what historians would very much like to know but had never been able to determine – until now.

Dates and details

The letter Sobecki found gives us the name of her son and tells us that he has a wife and a daughter, as well as the date around which he departed for Lynn and the route he took. Historians had already established how much time that would take, and now we know John’s arrival coincides with the unknown merchant and scribe who took Margery’s first notes. John died shortly after, as did the scribe.

It means that these dates and details match. It also means that it’s really Margery’s voice that we hear in the Book, not that of the priest. We know now that it was probably her son who wrote down the first draft from the mouth of his mother, and it is far more likely that the rest of the account is hers, too.

Now, Sobecki hopes to find more. There are probably more traces of the Kempes, treasures just waiting to be found that prove Margery truly had a voice of her own.